How can possibilists account for actuality as an absolute feature of some possible entities and not others? As we saw, we cannot treat actual existence as another accident or accident-like entity, since such entities would have to be included in all possible worlds, whether actual or not. Instead, the factor that explains something’s actuality will have to be external to that thing as a possibility. There are at least four ways to do this. Before we can lay out these four possibilist options, we must first discuss the alternative metaphysical theories of predication.

Let’s consider the metaphysical options in explaining the truth of an ordinary, contingent predication of the form S is P, where S is the subject term, referring to a particular, and P is the predicate, expressing some general, repeatable property. Suppose, for example, that we have a name for a particular cat, Egbert, and that this Egbert is in fact cute. Consider the true predication: Egbert is cute. How should we explain what grounds this truth? There are five options.

The first option has been called ‘ostrich nominalism’, because critics of this view accuse its proponents of sticking their heads in the sand, refusing to offer any substantive explanation of the truth of any predication. Ostrich nominalists agree that some predications are (absolutely) true and some are false, but they deny that there is any interesting, general, metaphysical account of what makes a predication true when it is true. Egbert is cute is true because Egbert is cute, end of story.

The second, third, and fourth options are versions of classical Platonism (with a capital ‘P’). On this view, there is a universal of cuteness, The Cute Itself. (We’re pretending throughout that cuteness is a real, natural, and fundamental property. So, pretend that cuteness is just as fundamental as your favorite natural property, like negative charge, cubical shape, or the distance measured by the diameter of a hydrogen atom.) We can explain the truth of the predication Egbert is cute by appealing to the fact that Egbert instantiates Cuteness. Egbert is cute by virtue of instantiating cuteness. The connection between Egbert and Cuteness is prior in explanation to the simple fact of Egbert’s cuteness.

The three forms of Platonism vary in how they understand the instantiation relation. The first variant borrows a strategy from the ostrich nominalist, by refusing to offer any deeper explanation of the fact that Egbert instantiates cuteness. We can call such a position that of “ostrich Platonism”. The next variant introduces a new kind of entity, an instantial tie. Egbert instantiates Cuteness because an instantial tie connects it to the cuteness universal. The third variant of Platonism introduces instead a composite entity called a state of affairs. On this account, Egbert instantiates cuteness by virtue of belonging to a state of affairs that contains both Egbert and the cuteness universal.

The final account is one that goes beyond ostrich nominalism without introducing any ante rem universal. Instead of a universal of cuteness, this account (the theory of individual accidents) posits a particular that is Egbert’s individual cuteness. Egbert is cute because his cuteness exists. This account corresponds to what in contemporary metaphysics is called trope theory or the theory of abstract particulars.

Five Viable Versions of Inegalitarian Possibilism

The five accounts of predication correspond to five distinct versions of inegalitarian possibilism.

First, we could treat actual existence in the way that so-called Ostrich Nominalists treat all primitive, natural properties. We could say that there is no deeper explanation, no “truthmaker,” for propositions of the form Possible entity x actually exists. Nonetheless, we must not treat actual existence as an accident contained in a possible world but rather as an external fact about one of the worlds.[1]

Second, we could adopt a Platonic account of actual existence, positing a universal of Actuality. To exist in actuality is to be a possible entity that instantiates this universal. On this theory, which we can call Bare Platonic possibilism, the property of instantiation is treated in an Ostrich Nominalist fashion, with no further metaphysical explanation. Once again, the fact that some entity stands in this primitive instantiation relation to the universal of Actuality is to be taken to be an external fact about some possible world.

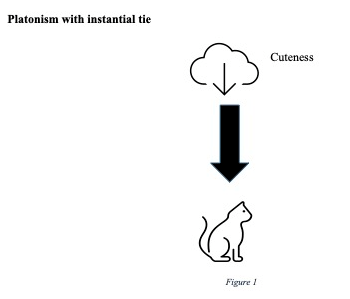

Third, we could adopt a Platonic account of actual existence, while adding to our ontology a new kind of entity, an instantial tie. Whenever a particular entity instantiates the universal of Actuality, we can posit that there exists a special entity that ties that entity to the universal. The existence of the instantial tie would then be the truthmaker for the actual existence of the entity in question. But to avoid a vicious circularity, we must treat the category of instantial ties in an actualist fashion. We must deny that there are (in our domain of quantification) any merely possible instantial ties. We will then end up with a hybrid theory: one that is possibilist about possible substances and accidents, and actualist about instantial ties.

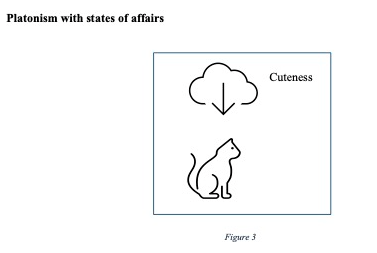

Fourth, we could combine a Platonic form of possibilism with David Armstrong’s states of affairs. An entity actually exists just in case it belongs to a state of affairs that also contains the universal of Actuality. Each existential state of affairs will contain one possible entity and the universal of Actuality. For an entity x to exist is for x to be a constituent of such a state of affairs. Here, too, we must adopt a hybrid account. To avoid circularity, we cannot suppose that there are any merely possible existential states of affairs. We can be possibilist about substances and accidents (and other states of affairs, if we wish) but actualist about existential states of affairs.[2]

Fifth and finally, we could adopt Thomas’s theory of acts of existence. In this case, we don’t need any Platonic universal of Actuality. Instead, we introduce a category of special entities, the acts of existence. Each actually existing entity is paired with an act of existence. Each act of existence actualizes the existence of one possible entity, and the act is individuated by that entity. Here, once again, we need a hybrid theory. We must deny that there are any non-actual acts of existence.

Thomas’s act-of-existence theory was inspired by al-Farabi’s account of existence as a “quasi-accident” added to possibly instantiated essences (species). Both were anticipated by the author of the Liber causis (Proposition IV), which had been wrongly attributed to Aristotle. Thomas was the first to recognize that Liber causis was a summary of Proclus’s Elements of Theology by an unknown Arabic author. As we mentioned in Chapter 5, this act-of-existence theory was endorsed and further developed by Avicenna.

[1] I haven’t mentioned the necessitism that has been proposed by Bernard Linsky and Edward Zalta (Linsky and Zalta 1996) and by Timothy Williamson (1998). On this view, all possible entities exist necessarily. But some entities are only contingently concrete. We take the Linsky-Zalta-Williamson theory to be essentially equivalent to our existential ostrich nominalist. Where our ostrich nominalist refers to actual existence (in a non-Quinean sense of ‘existence’), Zalta and Williams speak of actual concrete existence. In both cases, the new predicate is primitive and unanalyzable.

[2] The two Platonic accounts that introduce new elements (instantial ties and states of affairs) create anomalies that are at least potentially disqualifying. In both cases, the Platonist would have to assume that in the case of all other universals (besides the universal of actual-existence), we find in reality both actual and non-actual instantial ties (or states of affairs). Only in the case of this one universal are the instantial ties (or states of affairs) incapable of a merely-possible status. The result in both cases is a radically disunified account of predication.

One thought on “Five Theories of Predication”